A new study provides unprecedented insights into the brains and cognitive capabilities of dinosaurs and other prehistoric reptiles.

The key takeaways:

- Many theropod dinosaurs like T. rex had brains as large and complex as monkeys and primates. This suggests they were likely as intelligent as modern primates.

- However, other dinosaurs like sauropods had much smaller, simpler brains comparable to modern reptiles. Dinosaurs displayed a wide range of brain sizes and intelligence levels.

- The largest dinosaurs may have lived over 40 years with brains capable of flexible thinking, communication, and social behaviors on par with many modern mammals and birds.

- Flying pterosaurs had a wide range of brain sizes and presumed cognitive abilities, with the largest having brains comparable to monkeys.

Source: Journal of Comparative Neurology. 2023 Jun;531(9):962-974.

Studying Fossil Dinosaur Brains

While fossilized bones can reveal a lot about extinct animals, actual brain tissue does not preserve over millions of years.

So how can scientists study dinosaur and pterosaur brains if no direct evidence remains?

The researchers behind the new study measured the brain-case volume of various dinosaur and pterosaur fossils using CT scanning.

This gives an accurate estimate of actual brain size and mass when the animals were alive.

The researchers then compared the scaling of brain size to body size across different dinosaur groups and pterosaurs to that of living reptiles and birds.

This allowed them to infer how dinosaur brains were organized and their relative complexity.

Finally, by applying known relationships between brain size and cell numbers in modern animals, the scientists could estimate the number of neurons in key brain regions of dinosaurs and pterosaurs.

Neuron counts correlate closely with cognitive abilities and intelligence across living species.

So this data provides unprecedented insights into just how smart these extinct giants may have been.

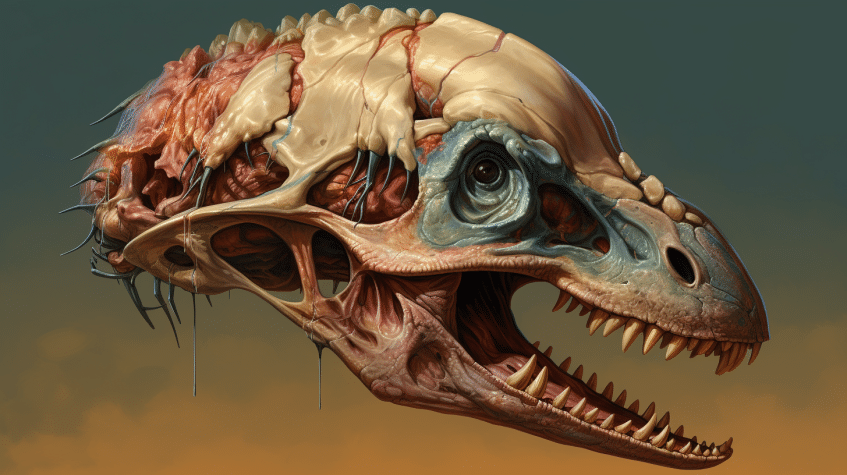

Not All Dinosaur Brains Were Equal

One major finding was that different groups of dinosaurs had vastly different sized brains relative to their body mass.

Theropods, the primarily carnivorous group containing T. rex, had the largest brains relative to body size.

In fact, most theropod species had brain-to-body size ratios similar to modern birds.

This suggests they likely had higher metabolic rates and more bird-like cognition.

In contrast, plant-eating sauropods like Brontosaurus had the smallest brains relative to their immense body mass.

Their brain-to-body ratios were similar to living reptiles like crocodiles and lizards.

This implies sauropods likely had slower, reptile-like brain processing.

Other major dinosaur groups like stegosaurs and ceratopsians had intermediate brain sizes and intelligence levels.

Among flying pterosaurs, some species had brains and presumed cognitive capabilities approaching monkeys and various carnivores.

But others had brains more akin to mice or lizards.

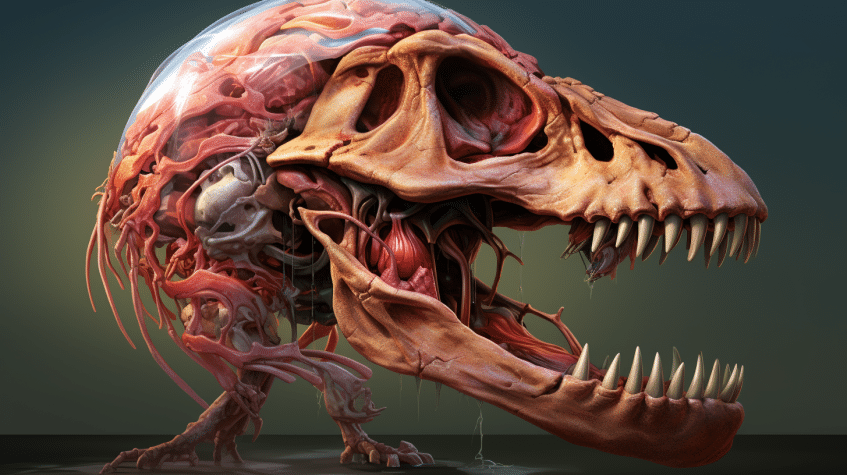

T. Rex: A Dinosaur With Primate-Like Cognition

Applying scaling rules for birds and reptiles, the researchers estimated numbers of neurons in key brain areas across dinosaurs and pterosaurs.

The results suggest the largest theropods like T. rex and Allosaurus had brains packed with neurons, capable of supporting complex cognition and behaviors.

For example, T. rex is estimated to have had over 3 billion neurons just in the telencephalon – the forebrain structure involved in decision-making and social behaviors.

This is similar to a baboon, and over 6 times higher than predicted for T. rex if it had typical reptilian scaling.

Other theropods like Acrocanthosaurus and Alioramus had around 1-2 billion telencephalic neurons, comparable to monkeys like capuchins.

This implies these giant carnivores likely had the mental capacities for advanced social interaction, communication, strategic hunting, and problem solving.

Meanwhile sauropods had many fewer neurons in keeping with their smaller brains.

A gigantic Brachiosaurus is estimated to have had just 306 million telencephalic neurons, comparable to a marmoset monkey.

Still a high number for a reptile, but far below the mental capabilities predicted for a similarly massive theropod.

Lifespans Up to 50 Years for Largest Dinosaurs

Another startling implication is for dinosaur lifespans.

Studies of living species show that absolute brain size and neuron counts strongly predict lifespan, with larger brains enabling longer lives.

Applying this scaling, T. rex is predicted to have lived over 40 years on average, with some individuals potentially reaching 50 years old.

This overlaps the longevity of large primates like gorillas and matches estimates from other evidence like T. rex population structure and growth rings in bones.

Smaller theropods still likely lived 20-30 years with brains capable of supporting their complex hunting and social behaviors over long lives.

In contrast, Stegosaurus is estimated to have had a lifespan under 25 years despite its enormous size, due to a simpler, smaller brain.

These neural-based estimates lend new support to the view that many theropod dinosaurs were more like warm-blooded birds than typical cold-blooded reptiles, with high metabolic rates, flexible cognition, and relatively long lifespans.

This paints a very different picture of giant predators like T. rex as intelligent, social creatures with lives extending over decades.

Flexible Behaviors Supported by Complex Brains

What does this mean in terms of dinosaur behaviors?

We can’t know exactly how dinosaurs thought and acted over 65 million years ago.

But the combination of large, highly neuronal brains with bird-like physiology in dinosaurs like T. rex lends support to inferences of flexible, even human-like behaviors.

With trillions of neural connections similar to primates, theropods likely engaged in advanced social strategies, communication, hunting cooperation, and problem solving.

Studies of their fossilized nesting sites suggest parental care of young, which demands long-term bonds and learning.

Vocalization and even primitive language may have been within their capacities given suitable brain anatomy.

The largest theropods needed extended parental care, mate cooperation, and learning to successfully hunt massive prey as adults.

This requires a highly flexible brain able to innovate solutions and adapt behaviors throughout a lifetime lasting decades, as seen in most mammals and birds.

While we can’t fully know the behaviors of extinct animals, the new study’s quantitative estimates of dinosaur brain anatomy provide evidence that the largest theropods convergently evolved avian-like brains and possibly cognitive abilities far exceeding traditional reptiles.

This mirrors recent evidence for bird-like growth rates, respiration, and insulating feathers in many theropods.

Together, the emerging view of dinosaurs like T. rex is not of lumbering giant lizards, but of active, social creatures whose intelligence and behaviors likely matched or exceeded the innovative behaviors of modern mammals and birds.

We will never know the full richness of dinosaur lives, but studies like this allow us to place better constraints on the neurological foundations underlying extinct dinosaur behaviors and ecology.

References

- Study: Theropod dinosaurs had primate-like numbers of telencephalic neurons

- Authors: Suzana Herculano-Houzel (2023)