Feeling lonely and socially isolated is associated with poorer health outcomes and increased risk of early mortality.

Research in monkeys now reveals how loneliness impacts the immune system, providing clues into the mechanisms underlying the health risks of loneliness.

Key Facts:

- Lonely monkeys show altered activity in the sympathetic nervous system and compromised immune cell function compared to non-lonely monkeys.

- Lonely monkeys have higher levels of inflammatory immune cells called monocytes.

- Genes involved in antiviral responses are underactive in immune cells from lonely monkeys.

- After infection with simian immunodeficiency virus, lonely monkeys show poorer immune control of the virus.

Source: Current Opinion Behavioral Science. 2019 Aut; 28:51-57.

The Social Brain

Humans are an inherently social species. Our brains have evolved complex circuitry dedicated to navigating our social world.

Feeling disconnected from others triggers evolutionary alarm bells, motivating us to seek out social contact.

But sometimes the urge to reconnect goes unfulfilled, leading to feelings of loneliness and social isolation.

Far from just an emotional discomfort, loneliness can have serious impacts on physical health and survival.

Research in both humans and animal models reveals that loneliness activates neural circuits and biological pathways involved in threat detection and stress responses.

The chronic stress of loneliness then triggers systemic changes, such as high blood pressure and inflammation, that increase risk for illness and early mortality.

Related: Loneliness: A Growing Health Problem

Animal Models Reveal Biological Mechanisms

Studying loneliness in humans can be challenging because it relies on self-report and a myriad of social and psychological factors contribute to each person’s experience.

Animal models allow researchers to carefully control conditions and take measurements that would be difficult or impossible in human subjects.

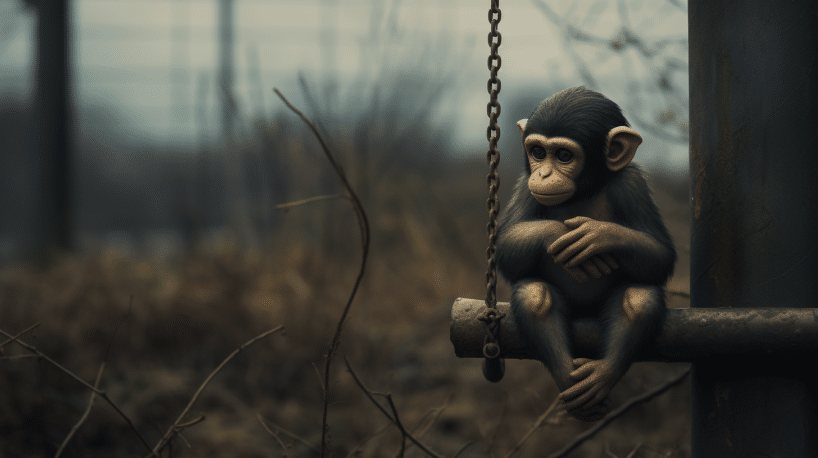

Monkeys are highly social animals that may experience loneliness, like humans.

Researchers have developed ways to identify lonely monkeys based on their social interactions with other monkeys in their group.

This provides the opportunity to compare health measures between lonely and non-lonely monkeys living in the same social environment.

A team of researchers led by John Capitanio at the University of California, Davis conducted a series of studies comparing immune system function between lonely and non-lonely rhesus monkeys.

Their findings reveal specific biological changes associated with loneliness that may help explain its health impacts.

Related: Loneliness: The Hidden Health Epidemic

The Sympathetic Nervous System and Inflammation

The sympathetic nervous system controls our physiological stress responses (“fight or flight”).

Chronic activation of this system is linked to negative health outcomes.

Capitanio’s team found that lonely monkeys have higher levels of norepinephrine – a hormone released by sympathetic nerves – compared to non-lonely monkeys.

This suggests loneliness triggers persistent sympathetic activation.

Inflammation forms another link between loneliness and poor health.

Prior human studies found associations between loneliness and markers of inflammation like the immune signaling molecules IL-6 and C-reactive protein.

The monkey studies confirmed that immune cells from lonely animals have an exaggerated inflammatory gene expression profile.

A specific type of inflammatory white blood cell called monocytes are overabundant in lonely monkeys.

Together, the increased sympathetic activity and inflammation observed in lonely monkeys mirror the physiological changes seen in lonely humans.

These changes likely contribute to increased risk for illness.

Antiviral Immune Defenses Impaired

Inflammation is one component of the immune response.

But a properly functioning immune system also requires cells and molecules that can specifically recognize and eliminate pathogens.

Analyses of gene expression patterns in immune cells revealed impairments in antiviral immune defenses in lonely monkeys.

Genes involved in the interferon response – a key antiviral defense – are less active compared to non-lonely monkeys.

To test whether these alterations have functional consequences, the researchers studied a group of monkeys experimentally infected with simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV), the monkey version of HIV.

Among these monkeys, animals identified as lonely prior to infection showed poorer control of SIV compared to non-lonely animals.

The findings suggest loneliness diminishes the immune system’s capacity to fight viral infections. Similar impairment likely occurs in lonely humans, increasing risk for illness.

Immune Cells Develop Abnormally

What causes the shifts in immune function observed in lonely animals?

The bone marrow may hold clues. Inside bone marrow, hematopoietic stem cells develop into the many types of immune cells that circulate in the bloodstream.

The researchers found evidence that immune cells are developing abnormally in the bone marrow of lonely animals.

The exaggerated sympathetic nervous activity associated with loneliness appears to interfere with white blood cell maturation.

Glucocorticoids like cortisol normally help regulate inflammation by suppressing immune cells.

But immune cells from lonely monkeys and humans seem to have lost sensitivity to glucocorticoids, contributing to uncontrolled inflammation.

Ongoing and Future Research

The monkey studies continue to probe the mechanisms linking loneliness to health outcomes.

Capitanio’s team is examining bone marrow directly to understand how loneliness impacts immune cell development.

Testing whether interventions that reduce loneliness reverse the physiological changes will also be important.

Their research highlights potential biological targets for treatments to improve well-being and health.

While loneliness is complex and challenging to study in humans, animal models provide critical insights into the biological foundations of loneliness.

This expands our understanding of how social experiences get under the skin to affect the brain and body.

References

- Study: Loneliness in monkeys: Neuroimmune mechanisms

- Authors: John P. Capitanio et al. (2019)