TLDR: A study identified specific gut microbial features in Parkinson’s disease (PD) across different countries, highlighting increased α-diversity, altered bacterial species, and decreased metabolites in PD patients.

Highlights:

- Increased α-Diversity: The study found higher α-diversity in PD patients across six datasets from different countries.

- Altered Bacterial Species: Species such as Akkermansia muciniphila were increased, while Roseburia intestinalis and Faecalibacterium prausnitzii were decreased in PD patients.

- Decreased Metabolic Pathways: Genes involved in riboflavin and biotin biosyntheses were significantly decreased in PD, affecting the production of key metabolites.

- Reduced Metabolites: Fecal short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) and polyamines were significantly decreased in PD patients.

- Country-Specific Bacterial Differences: Different bacteria were responsible for the decreased biosyntheses of riboflavin and biotin in various countries, suggesting regional variations in gut microbiota’s impact on PD.

Source: Nature (2024)

Link: Parkinsons Disease & The Gut Microbiome (Historical Research)

Early Observations

Non-Motor Symptoms

Historically, Parkinson’s disease (PD) was primarily recognized for its motor symptoms, such as tremors and rigidity.

However, non-motor symptoms like constipation have been reported as early as the 19th century.

These gastrointestinal issues often appeared long before the onset of motor symptoms, suggesting a potential link between the gut and PD.

Braak’s Hypothesis (2003)

Pathological Pathway

Dr. Heiko Braak proposed that PD might begin in the gastrointestinal tract.

His hypothesis suggested that abnormal α-synuclein proteins, which are a hallmark of PD, could originate in the gut and travel to the brain via the vagus nerve.

This theory was based on the presence of α-synuclein aggregates found in the enteric nervous system of PD patients.

Vagotomy Studies

Reduced Risk

Epidemiological studies found that patients who had undergone a vagotomy, a surgical procedure that cuts the vagus nerve, had a lower risk of developing PD.

This provided indirect evidence supporting Braak’s hypothesis, suggesting that the vagus nerve might be a critical pathway for the disease’s progression from the gut to the brain.

Gut Microbiome Research

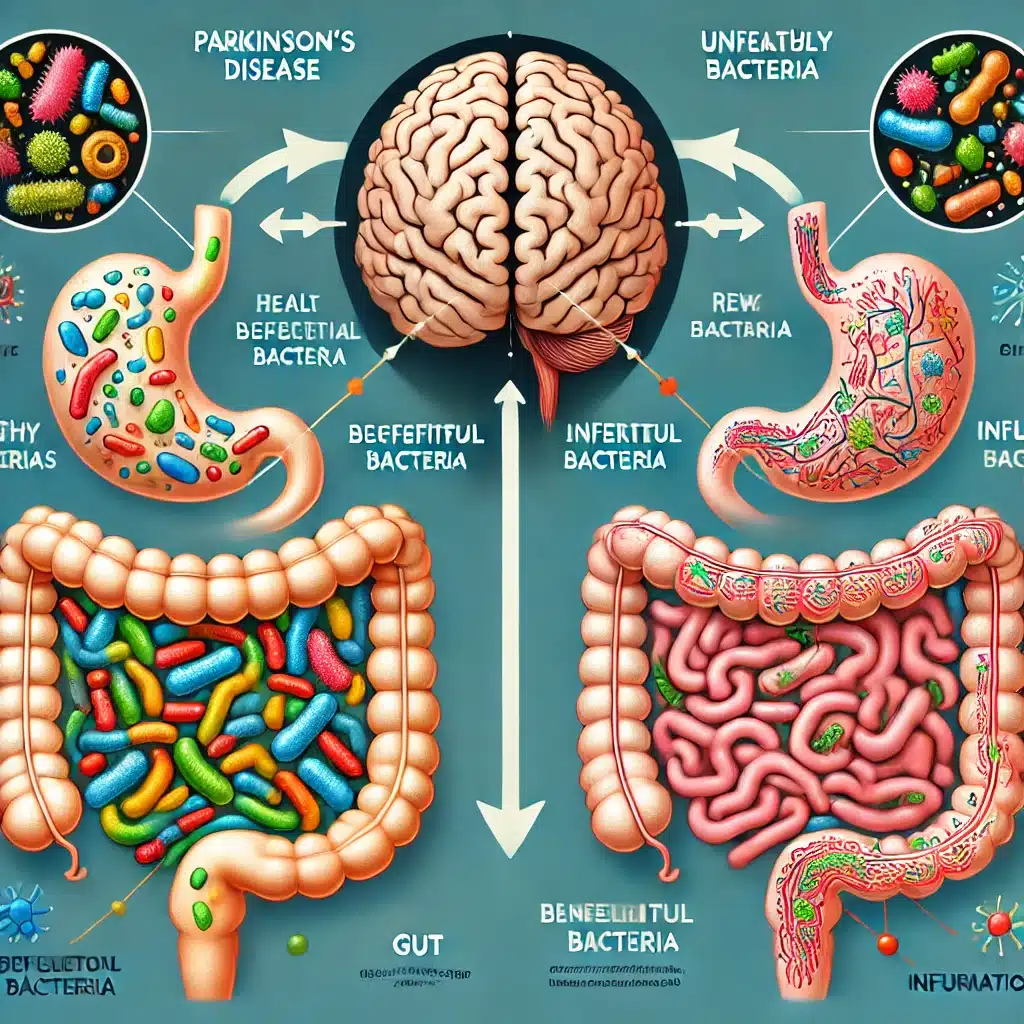

Microbiome Alterations

Advances in gut microbiome research have shown significant differences in the gut bacteria of PD patients compared to healthy individuals.

Early studies using techniques like 16S rRNA gene sequencing revealed that certain beneficial bacteria were reduced in PD patients, while harmful bacteria were increased.

Short-Chain Fatty Acids (SCFAs)

Protective Role

SCFAs, produced by gut bacteria through the fermentation of dietary fiber, play a crucial role in maintaining gut health and regulating inflammation.

Research has found that PD patients often have reduced levels of SCFA-producing bacteria, leading to lower SCFA levels.

This reduction is believed to contribute to gut inflammation and increased intestinal permeability.

Neuroinflammation and the Gut-Brain Axis

Immune System Involvement

The gut-brain axis refers to the bidirectional communication between the gut and the brain.

Studies have shown that the gut microbiome can influence the central nervous system through immune, endocrine, and neural pathways.

Chronic gut inflammation and altered microbiota can lead to neuroinflammation, which is implicated in the pathogenesis of PD.

Alpha-Synuclein and the Gut

Spread of Pathology

Research has demonstrated that misfolded α-synuclein can spread from cell to cell in a prion-like manner.

Animal studies have shown that injecting misfolded α-synuclein into the gut can lead to its spread to the brain, supporting the idea that the gut might be a starting point for PD pathology.

Clinical Trials & Therapeutic Approaches

Probiotics and Diet

Ongoing clinical trials are exploring the use of probiotics, prebiotics, and dietary interventions to modulate the gut microbiome in PD patients.

These approaches aim to restore a healthy gut microbiota balance, potentially alleviating both motor and non-motor symptoms of PD.

Main Findings: Gut Microbiome Analysis & Parkinsons Disease (2024 Study)

Our study investigated the gut microbiome of Parkinson’s disease (PD) patients across different countries, revealing several important findings.

1. Increased α-Diversity in PD Patients

What is α-Diversity?: It refers to the variety and abundance of different species present in the gut.

PD patients showed an increased α-diversity, meaning they had a wider range of bacterial species in their gut compared to healthy individuals.

This was consistent across all six datasets from the USA, Germany, China, Taiwan, and Japan.

2. Specific Bacterial Species Changes

Increased Bacteria

Akkermansia muciniphila: Known for its role in maintaining the gut lining, this bacterium was found in higher amounts in PD patients.

Decreased Bacteria

Roseburia intestinalis & Faecalibacterium prausnitzii: These bacteria are important for producing short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) that support gut health.

Their reduced presence in PD patients indicates a disruption in the gut’s beneficial activities.

3. Decreased Metabolic Pathways

Riboflavin (Vitamin B2) & Biotin (Vitamin B7): Both vitamins are crucial for various bodily functions, including energy production and metabolism.

In PD patients, the genes responsible for producing these vitamins were significantly reduced.

This reduction in gene activity suggests that PD patients might have lower levels of these essential vitamins, affecting overall health and gut function.

4. Reduced Metabolites in PD Patients

Short-Chain Fatty Acids (SCFAs)

What are SCFAs?: They are produced by gut bacteria from dietary fiber and play a key role in maintaining the gut lining, regulating inflammation, and supporting the immune system.

SCFAs, including acetate, propionate, and butyrate, were significantly lower in PD patients. This reduction can weaken the gut barrier and increase inflammation.

Polyamines

What are Polyamines?: These are molecules involved in cell growth and function.

Levels of polyamines like putrescine, spermidine, and spermine were also significantly decreased in PD patients, which might contribute to neuroinflammation and gut health issues.

5. Country-Specific Bacterial Differences

Different Bacteria, Same Problem

The study found that the bacteria responsible for the decreased production of riboflavin and biotin varied by country.

For instance, Faecalibacterium prausnitzii was the main culprit in Japan, the USA, and Germany, whereas Phocaeicola vulgatus was more influential in China and Taiwan.

These regional differences suggest that while the gut microbiome’s disruption in PD is a global issue, the specific bacteria involved can vary based on geography, potentially due to differences in diet, environment, and genetics.

Study Details: Gut Bacteria Features in Parkinson’s Disease (2024)

Sample

Participants: The study involved 94 PD patients and 73 healthy controls from Japan. Additionally, the data from five previously reported studies were included, covering participants from the USA, Germany, China (two datasets), and Taiwan.

Total Sample Size: The combined analysis included a total of 813 PD patients and 558 controls.

Methods

- Fecal Samples: Collected from Parkinson’s patients and controls in Japan and other countries.

- Sequencing: Shotgun sequencing was used to analyze the bacterial DNA in the fecal samples.

Analytical Techniques

- α-Diversity Analysis: Measured the variety and abundance of bacterial species in the gut.

- Taxonomic Analysis: Identified specific bacterial species that were increased or decreased in PD patients.

- Pathway Analysis: Examined the genes involved in riboflavin and biotin biosyntheses and their correlation with fecal metabolites.

- Metabolomic Analysis: Quantified levels of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) and polyamines using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) and liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS).

Statistical Analysis

Meta-analysis was conducted to combine and compare data from the different countries.

Confounding factors like age, BMI, and medication use were adjusted to ensure the accuracy of the findings.

Limitations

- Geographic Variation: The study found that different bacterial species were responsible for decreased biosyntheses of riboflavin and biotin in different countries. This variation can complicate the generalization of the results.

- Sample Size Disparity: The number of participants varied across countries, which might influence the robustness of the meta-analysis.

- Confounding Factors: Despite adjusting for several confounding factors, other unmeasured variables could still affect the results.

- Cross-Sectional Design: The study design provides a snapshot in time and cannot establish causality between gut microbiota changes and PD progression.

- Fecal Sample Variability: Differences in sample collection, storage, and processing across studies could introduce variability in the data.

Preventing Parkinson’s Disease via Gut Health? (Ideas)

1. Dietary Interventions

High-Fiber Diet: Consuming a diet rich in dietary fiber supports the growth of beneficial gut bacteria that produce short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), which are crucial for maintaining gut health and reducing inflammation.

Foods to Include: Whole grains, fruits, vegetables, legumes, nuts, and seeds.

Antioxidant-Rich Foods: Foods high in antioxidants can help reduce oxidative stress and inflammation, both of which are implicated in PD.

Foods to Include: Berries, dark leafy greens, nuts, seeds, and green tea.

Fermented Foods: These foods contain probiotics that can enhance the diversity and health of the gut microbiome.

Foods to Include: Yogurt, kefir, sauerkraut, kimchi, and miso.

2. Probiotics and Prebiotics

Probiotics: Taking probiotic supplements can help increase beneficial bacteria in the gut. Look for probiotics containing strains like Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium, which are known for their positive effects on gut health.

Prebiotics: Prebiotics are non-digestible fibers that feed beneficial gut bacteria. Including prebiotic-rich foods in your diet can support a healthy microbiome.

Foods to Include: Garlic, onions, leeks, asparagus, bananas, and whole grains.

3. Regular Physical Activity

Exercise Benefits: Regular physical activity has been shown to have positive effects on gut health and can reduce inflammation throughout the body. Exercise promotes the growth of beneficial gut bacteria and helps maintain a healthy gut barrier.

Recommended Activities: Walking, jogging, cycling, swimming, and strength training.

4. Stress Management

Impact of Stress: Chronic stress can negatively affect gut health by altering the composition of the gut microbiome and increasing gut permeability.

Stress Reduction Techniques: Practice mindfulness meditation, yoga, deep breathing exercises, and other relaxation techniques to manage stress levels.

5. Avoiding Harmful Substances

Pesticides and Herbicides: Limit exposure to pesticides and herbicides, which have been linked to increased PD risk. Opt for organic foods when possible and wash fruits and vegetables thoroughly.

Antibiotics: Use antibiotics only when necessary and prescribed by a healthcare professional, as they can disrupt the balance of gut bacteria. Consider taking probiotics during and after antibiotic treatment to restore gut health.

6. Regular Health Check-Ups

Regular check-ups with a healthcare provider can help monitor gut health and catch any early signs of gut-related issues.

Discuss any gastrointestinal symptoms with your doctor, as early intervention can be crucial.

Conclusion: Parkinsons Disease & Gut Bacteria

References

- Study: Meta-analysis of shotgun sequencing of gut microbiota in Parkinson’s disease (2024)

- Authors: Hiroshi Nishiwaki et al.